She came out crying, as most babies do, on the Thursday morning of October 11, 1923. She was the fifth of 10 children that survived. Her mother grieved losing three children that could not thrive in a world without fetal medicine, constant clean water, or antibiotics.

Men would cheer in the pubs that evening after Babe Ruth hit 2 home runs in a World Series game. But the German mark would fall from 10 Billion per pound to four billion per dollar. No one knew then that Germany’s troubles would lay the foundations of another World War, one that would take this babies‘ husband and her brothers away from her years later. They didn’t even know that they would experience a recession the likes that America had never seen just 6 years later. For the 1920s, things were as they ought to be. There was a sense of hope and advancement.

Her mother looked at her and named her, Pearl, a fashionable name for the time, although not popular. She would tell her over and over that pearls were greater than rubies and diamonds — and more precious — and that it why she named her thus.

In was an exciting year. Just a couple of months earlier, the “Hollywood” sign had been raised in California. Little Pearl could never imagined that she would have a daughter, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren who would live within a stone’s throw of this famous sign decades later. Nor would she have been excited. Because in the 1920s, Chicago was home to the world’s silent film stars, who had massive homes built on Longwood Avenue in a whole other Beverly Hills just a short drive away. Even though Pearl’s parents were never rich, she may have pictured herself as one of these stars. Her mother would stay up all night to curl each of her 5 daughter’s hair, and she would create new dresses from the donated clothes so that her daughters always looked like the prettiest girls at every party.

Pearl’s childhood was cut short though. With so many children in one house, her father took on multiple streams of income just to pay the rent and feed them all. One of which was to make cigars and cigarettes in his attic for the growing cigarette craze. The 1929 passing of the 19th amendment made smoking a symbol of women’s new role in society. Woman were encouraged by Lucky Strike Cigarettes to grab for a cigarette instead of a sweet. And that marketing fueled the need for more tobacco products to be made. Pearl and her siblings were part of the crew that made them.

They would sit, side-by-side, hating the smell of the leaves, and even worse, hating how they made their hands reek of smoky wood, especially before going on dates, but Pearl would try to get through the arduous chore none-the-less. This was not the the only work assigned to her, though. Each of the daughters would eventually take turns caring for their mother who become ill for many years from cancer. They toiled day and night to make food for all the men in their family, attend to their schoolwork, and keep their mother as comfortable and as clean as she could be. Her mother, Celia, would die when Pearl was just 23 years old. Her father would die just three years later of the same cancer.

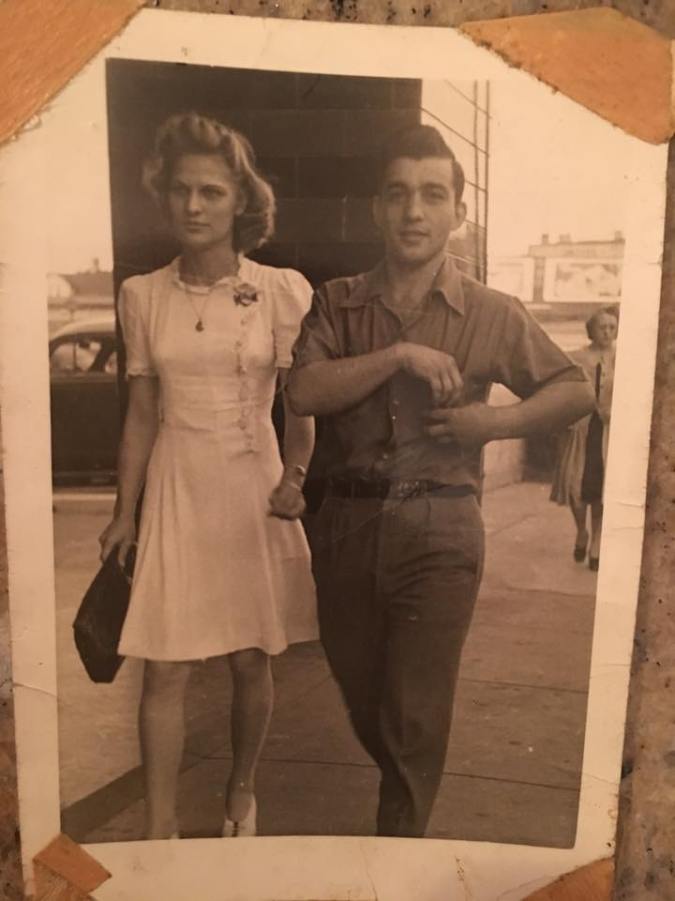

As a teenager, Pearl aimed to be as good-as-a-girl should be. By 16, she met George Collura, a handsome imp who had a strut to his step and slicked back hair. She quickly fell for him. George and Pearl loved to go out dancing with friends, although George was five years her senior, so he often begged her to fool the bouncers into thinking she was over 18. By the time she reached that age though, she had married George and quickly became pregnant with a precious girl of their own, Georgene, who they would spend a lifetime adoring.

Within days of marrying George, Pearl moved into his families’ home. The family, who met at the dinner table every night and enjoyed each other’s company very much, did not speak English well. Her in-laws were from Sicily, and only spoke Italian. George and his five siblings were the only people with which she could speak English fluently. But Pearl didn’t mind. One of her sister-in-laws had born a child at the same time, a boy, and so the two would bring their babies to the park and share the chores around the house.

What was difficult was that within one year of marrying George, America entered World War 2. He and his brother, Vince, were sent to clean up after the devastating attacks on Pearl Harbor. The other brother-in-law, Joe, was sent back to the Europe his parents had fled to fight against the Axis powers.

The girls continuously prayed for all of the boys to come home safely. And they did: Joe with a Purple Heart that he had earned in an attack that left his hearing impaired for the rest of his life. When the boys came home, all of them felt like it was finally time to start their lives again.

George came home from the war and worked at jobs that earned him twenty one dollars a week at the time. Upon coming home, they, like so many others, quickly had another daughter — a stunning girl that they named, Diane.

They were happy for a long time, having moved to a two-flat near a park. The neighbors would get together every night to talk and dance and the street, happy that their freedom was secure, relishing the community they had. Prayers of despair during the war had turned into thanksgiving for the fruits and blessings in their life. Later, when they had given birth to all their children, Pearl tried to go to work, taking a position in a factory. But on her first day, she found out that her daughter had gone to school without a sweater, and so she quit. It wasn’t the early 1950’s stereotype or demands of a woman that pushed her. She was one of those rare women who just really loved being a mother. Her children meant everything to her, and she tried to be as loving and gracious as her mother had been to her.

For many years, this is how it went: George and Pearl and their two beautiful girls. Six years passed between Diane and the birth of their third daughter, Sandra, in 1953. Pearl had known something was dangerously wrong during the late stages of her pregnancy. She fought to get to the doctors who eventually took her into the delivery room. As was the tradition of the time, she was knocked out while she gave birth. It would weeks later before she found out that Sandie was a twin and a child was lost during birth. The nurses never told her. Their coldness mimicked the doctors who would not acknowledge her concern about Sandie getting sick. She fought tooth-and-nail when Sandie eventually became worse, and she had to bring her to Children’s Memorial Hospital for an immediate surgery on her heart. Afterwards, the nurses said that Sandie would not eat. But Pearl, fierce and diligent, sat in a rocking chair feeding her daughter through an eye dropper. While generally happy-go-lucky, you could see Pearl strong and mighty side when it came to protecting and loving children.

Four years later, the couple decided to try for another child. Maybe to carry on the patriarchal family name, or maybe just to give Sandie a playmate. They gave birth to Cynthia, the youngest and the cutest of them all. (Writer’s note: I can say that confidently, for she is my mother.) The sisters were not jealous of this youngest kid – she was their doll. They dressed her and watched her as if she was their own. George loved his four daughters, and Pearl delighted in their family. They created beautiful holidays together, and stayed close.

Sometime in the 1960’s though, things changed. George got hired on as a garbage truck driver for the city of Chicago — a job that often led to some men to fall prey to becoming alcoholics. Their marriage began to suffer, until one morning, in late 1967 when they found themselves in front a judge, asking for a divorce. The judge asked Pearl what she wanted from George. She said nothing. She advocated that he was a wonderful father, and she was not worried about him not taking care of them. The judge found this incredulous, but it was true. Their marriage may have ended, but their friendship was still in tact and it would remain that way. In a surprising twist, Pearl fell in love with George’s brother, Joey. She married him, and in years to come, the three would spend their days and their vacations together. Their decision was always to unite their family instead of dividing it.

Pearl moved into Joe’s house, a widow who had three very intelligent children of his own – two lovely girls and one courageous boy. They had lost their mother to illness, and so, she tried to be as good of a step mother to them as she could. She also became a nurse aide in the newborn ward of a hospital. She would made sure each child was diapered, fed, rocked, and had a pacifier in place, often to the chagrin of her co-workers who did not want to spend extra time pampering each child. But that was Pearl’s heart: each child was to be treated as if they were the only one in the world.

By this time though, Pearl had also entered into being a grandmother. In all, she would be a grandmother, step-grandmother, and great grandmother, to 18 grandchildren and 23 great grandchildren. She welcomed each grandchild through the decades, proudly attending every cheerleading, baseball, football, gymnastics, swimming, and dancing event that she could. You could very often hear her proudly cheering, “That’s my Grandkid!” as they stepped up to perform. She was even known for wandering onto a field to give them a kiss. The umpires would call time out, citing, “Grandmother on the field!”

She made every birthday special, often singing the loudest and admonishing each child in a morning phone call that they should be aware because, “How you are on your birthday, you are all year. So put money in your pocket and a smile on your face.” She would help plan birthday parties, often in a pair of white shorts, a polka-dotted shirt, and a smile. Her most incredulous talent may have been the way that she could take an ordinary game of dropping clothes pins into a milk jug and make it into a spectacle that only the Bozo show could match. For a short time, she even worked at McDonalds, just so that she could make other children’s birthdays special.

When the kids were mischievous, as children often are, her kids and grand kids don’t ever remember her ever yelling at any of them — a feat that is pretty remarkable. She had a way of rubbing their back or giving them a hug, and helping them to clean up the consequence of their actions. She was not rude or quick tempered at all. But she was not lenient either. She simply walked every step with a child so they could be all that they could be.

Each grandchild remembers times of creating play dough masterpieces with her. Or being amazed at how she could take two small bits of toilet paper to make them believe that they were birds who truly could fly away and disappear. “Fly away, Jack. Fly away, Jill. Come back, Jack. Come back, Jill,” she would say as she would swirl her arms in the air and hide her hands behind her back. Each could recall laughing hysterically through a game of Rob the Bush or Screw Your Neighbor. Thoughts of her are memories of times of feeling like they belonged and were beloved.

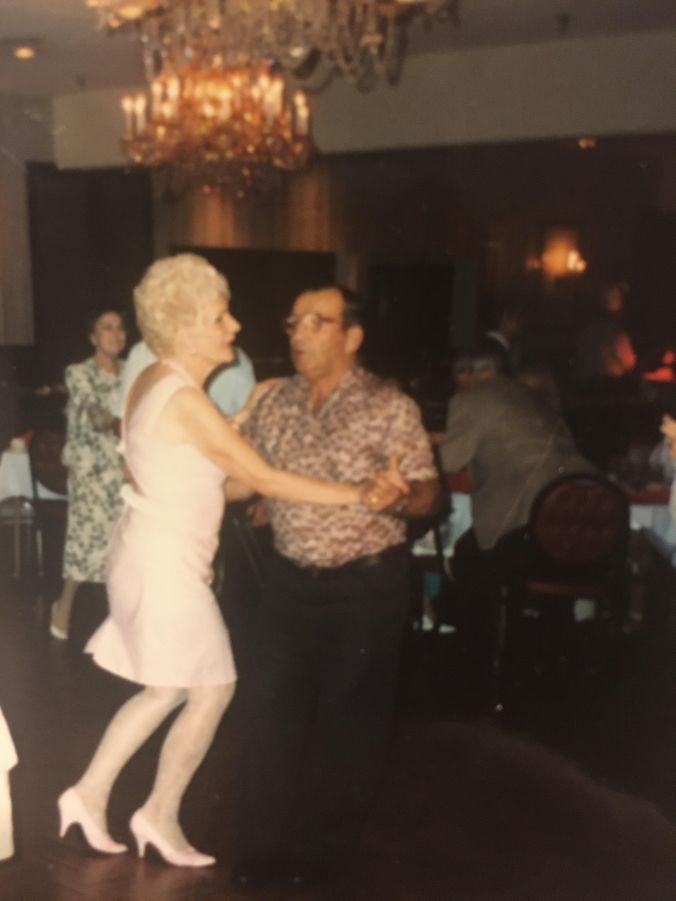

She could make a sad song precious, and a precious moment immortalized in a child’s memory. She’d sing such early 1900 classics as “Please, Mister Take Me in your Car/Always in the Way,” a song about an orphan child trying to grapple with losing her mom; and “How Much is that Doggie in the Window.” Sometimes she’d make a silly pout face, but then quickly change it to a great big smile, and then she hug them all real close and sway back and forth. She was never ashamed to get on the dance floor at a wedding, especially for a polka or for the chicken dance. She’d wiggle and shake and make sure everyone else would, too, and then they’d all laugh and laugh.

As George and Joey got older, she was an attentive sister and wife to both of them. She nursed each one through sickness and death, acting as the on-call nurse at night, and the diligent caregiver during the day. The death of her beloved companions hit her hard, but she took hope and solace in being with her daughters, grandchildren, and great grandchildren every day for the next 20 years.

She played cards and folded laundry, colored a million coloring sheets and made spaghetti and meatballs too many times to count. She’d sit in the silence and say her prayers, asking God to bless each one of the kids she loved. She traveled from house to house out of a suitcase for a time, spending time with each family, until, one day, dementia set in, and others had to travel to visit her instead.

Pearl spent the last three years of her life in a nursing home, cheering up the staff and fellow residents instead. Her diligent daughters spent every day with her, for hours on end, making sure that she was never alone, the same way she had never let them be alone. She would hold their hand, grateful that those she loved were near. And when they needed to go home at night, her only question was “when are you going to come back?” “Tomorrow, mom. We’ll be back tomorrow,” was always the reply.

In the end, she didn’t want to leave, didn’t want to go onto eternity. Heaven, for her, was spending time with her girls. She loved them and delighted in the way they loved her. She fought to stay with them as long as she could, until an irreparable broken femur invited infection that she could not battle. She passed, quietly, with angels guarding her bed, and shortly after 11 am on Sunday, September 15, 2019. But she will truly always live on in the love that each of her family members display to the communities and workplaces that they serve in every day.

Her legacy is simple. She loved deeply, and she made it seem easy. And so, those that follow her love deeply, without it seeming a burden to them. She exemplified wholeheartedness. And she’ll live that way, forever more, in them.